It has been several years since we have had an outbreak of late blight in Idaho. It is easy to forget that late blight can be a threat in this region given all the other issues that growers have to deal with during the growing season.

However, history tells us that the most widespread late blight outbreaks have been associated with two factors: 1) presence of volunteer potatoes from the previous crop and/or planting of seed potatoes sourced from regions where late blight frequently occurs, and 2) frequent rain events throughout the growing season.

We want to stress that late blight has not been found in Idaho so far this year. However, the unseasonably wet and moderate weather we’ve had recently has created conditions for potential late blight outbreaks in many locations. For example, in western Idaho where the crop is just closing the rows, we have had several weeks of intermittent showers as shown by records from the Parma Agrimet site.

Although many areas of Idaho experienced a colder than normal winter, higher snow falls across the Snake River Valley meant that the soil temperatures in many areas remained above freezing. The University of Idaho Volunteer Survival Model (https://cropalerts.org/volunteer-survival/), shows the risk of volunteer potato survival this year was high in most areas in southern Idaho. Infected volunteer potatoes, cull piles and seed tubers along with the recent wet weather conditions can all potentially contribute to the development of a late blight this year. As such, it would be prudent to plan ahead for the management of any potential late blight outbreaks.

Effective management of late blight requires the implementation of an integrated disease management approach, including strict sanitation practices (e.g. management of cull piles), good irrigation management, and the proper timing and application of effective fungicides. All these practices together can reduce the chances of a late blight outbreak.

Scouting is the first line of defense against late blight. Field scouting should begin after emergence when the first plants are 4 to 6 inches tall. In potato fields after plants close across the rows, look for late blight in the lower portions of the plant where the foliage stays wet longer. Scouting should be concentrated in areas of the field most likely to remain wet for the longest period of time, such as the center tower of pivot irrigation system, irrigation overlaps, and areas missed by fungicide applicators such as the edges of fields. Low spots where soil moisture is highest and parts of the field shaded by windbreaks are examples of areas where scouting should be intensified. The symptoms of late blight (see pictures with this article) can be confused with other diseases and physiological disorders. If you find plants displaying symptoms of late blight, we recommend you take them to a local expert than can confirm the diagnosis.

Scouting allows growers to make informed disease and pest management decisions and provides early detection of other problems that may be present in the field, such as nutrient deficiency or herbicide injury. By using information collected by scouts, growers can time fungicide applications for optimal effectiveness. This is especially important for the control of late blight as fungicides are most effective when applied to foliage before infection occurs or when the disease is in its very earliest stages of development and no symptoms are visible. In the irrigated fields of southern Idaho, late blight can be very difficult to manage once infections become established as the humid microclimate within the canopy favors further disease development after irrigation.

There are a wide range of fungicides labeled for use against potato late blight. Each fungicide is different and will have specific conditions for use listed on the label with additional details regarding application rates, re-entry intervals and total product amounts that can be applied in a season. Some may even include information on how to minimize the risk of fungicide resistance developing. Fungicides that are effective for the control of late blight tend to have one of three modes of action: germination inhibition (they prevent germination of spores and thus plant infection), inhibiting mycelial growth (they block pathogen colonization of the plant cells), anti-sporulation activity (they prevent the pathogen from sporulating and thus limit spread of the disease). For more information on properties of fungicides registered for use in potatoes go to the following link: https://cropalerts.org/2020/04/24/potato-late-blight-control-recommendations-for-southern-idaho-in-2020/.

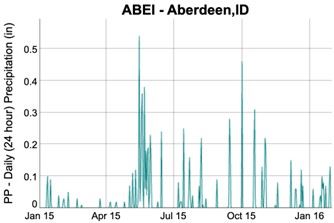

In years when late blight has been confirmed in Idaho it has usually appeared after mid-July. In the last wide scale outbreak that occurred in SE Idaho, late blight was first reported in Bingham County on July 10. On that date, the high temperature recorded at Aberdeen R&E Center was 67 degrees F and it had been a wet June with daily rainfall totals as high as 0.5 in. (see Figure 1 and 2). These are ideal disease conditions.

To provide additional information on the threat of late blight the University of Idaho operates a spore trapping network in cooperation with the Idaho Potato Commission. Weekly updates from this network will be on the IPM website (https://idahopestmonitoring.org) starting the week of July 3.