Source: Atlas Obscura

Manuel Choqque Bravo, a fourth-generation potato farmer in the Andean highlands of Peru's Chinchero District, is about to perform a magic show. He lines up multiple deformed tubers, indigenous to the area best known for its proximity to Machu Picchu, and one by one slices them in half, revealing a color spectrum of intense violet and gold hues.

He’s a veteran to such presentations, so he knows to pause and let his audience savor their first glimpse of the beloved papa andina that has captured his heart and driven him to change the world’s view of tubers.

“People think the potato has no healthy properties, but the truth is far from that,” he says in the soft-spoken, lyrical cadence typical to his hometown. Bravo has made it his mission to resculpt the world’s view of the potato by creating unique potato hybrids—packed with nutrients and flavor—on his family’s farm.

Bravo, just shy of his 32nd birthday, grew up running through his family’s fields. The expectation that he continue in his father’s footsteps weighed on him as a young man.

“I always had that pressure, but at first I believed being in the fields was synonymous with an atraso, backwardness,” he says, “just like many youngsters in Peru today who emigrate to the cities because they believe working in the fields will result in the same conditions as that of their parents.”

In high school, he decided to pursue law, but as fate would have it, he arrived late to school and ended up in the wrong class. “I accidentally signed up for a botany class and from that moment on was hooked. I thought, ‘Wow, plants are just like the human body—they have veins.’”

Bravo delights in slicing potatoes in half to display their vibrant innards.

Bravo delights in slicing potatoes in half to display their vibrant innards.

Afterward, he headed off to the Universidad San Antonio Abad in Cusco, the first of his family, the first of his entire village, to attend university. He studied agricultural engineering and then worked at the Centro Internacional de la Papa (the International Potato Center).

If there’s going to be an international center for potatoes, it makes perfect sense that it would be in Peru. Estimates of the number of tuber varieties in the country fall anywhere between a robust 3,000 and 5,000 types, and it is believed that the tuber was domesticated around 8,000 years ago on the mountain slopes near Lake Titicaca. Since then, Peruvians have embraced the potato in their cuisine with dishes such as causas and papas a la huancaina (yellow potatoes in a spicy, creamy sauce).

Bravo is not the first to tinker with the potato. The Incas used the same valley for their own version of agricultural engineering, building enormous circular terraces carved out of the mountainside in nearby Moray. These stacked fields emulated the microclimates of different slopes, which, archeologists theorize, allowed it to be used as a kind of agricultural research station.

“The truth is we are connected from the beginning,” says Bravo. “All the work I have done, I began with native potatoes that were varieties the Inkas had.”

There are countless varieties, and almost all of them have some form of natural pigmentation. What stands out with Bravo’s is the intensity, or increased pigmentation, of his colorful potatoes. It’s a result of his determination to not only preserve, but to perfect the potential of Peru’s revered crop.

These terraces that the Incas built in Moray may have allowed them to emulate the many and varied farming conditions of their empire.

These terraces that the Incas built in Moray may have allowed them to emulate the many and varied farming conditions of their empire.

“At first I thought everything I had learned at the university was the same as what I learned from my father working in the farm,” says Bravo. “It affected me a lot. I thought, ‘No, I cannot continue with the same concept.’” He emerged determined to research new, innovative ways to breed potatoes.

He spent some time working at the Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria, better known as INIA, the state department’s agricultural hub. It was here that Bravo saw a future in developing pigmented hybrids on his family’s farm.

In 2008, he began collecting different potato varieties from the surrounding communities and adapting them to his district of Chincero in Urubamba, a process that proved fruitful because the tubers shared the same climate.

“Back then, my objective was as a conservationist. [I wanted] to obtain and grow a diversity of native potatoes. It was more of a hobby.” Before long, though, he found himself obsessing over the tubers, determined to improve upon each one.

Urubamba is a town in the Sacred Valley, the 37-mile stretch of fertile land where he is from. It’s also home to the luxury property Tambo del Inka, whose proprietors were the first to take notice of his work.

“I knocked on so many doors, over 30 hotels and restaurants, without success,” says Bravo. “People would say, ‘Oh, fantastic, we’ll call you,’ but they never called me back.”

He tried selling his produce at the local market but shoppers were skeptical. Some said his potatoes were diseased, simply because they had never seen potatoes like that. Frustrated, Bravo found himself at the gated entrance of Tambo del Inka.

“I didn’t know what it was, if it was a hotel or a restaurant or what. I just saw a huge luxury property. He smiles as he recalls the moment the watchman greeted him. He handed the guard a copy of the creased square paper he carried, which read: “Selling native potatoes, by Manuel Choqque Bravo.” He asked if he could hand it to the chef.

Chef Victor Alvarez did receive the note and was intrigued, immediately calling Bravo back.

Now, Bravo visits the property regularly, usually with one of his eight siblings, to showcase his potatoes to those staying at the hotel. Alongside the burbling Vilcanota River, with the inspiring Chicón mountain as a backdrop, he lays out his tubers over brilliantly colored alpaca tablecloths and exposes their inner secrets one by one.

These colorful tubers fit into a millennia-long history of potato-improvement plans.

These colorful tubers fit into a millennia-long history of potato-improvement plans.

Potatoes are self-pollinated, which means they have the male and female flowers in one plant. Farmers tend to plant chunks of last season’s crop, which grow identical tubers. There’s no cross-breeding, unless you intervene, as Bravo learned to do, through meticulous hand-pollination. With the patience and care of a surgeon, Bravo manually removes pollen from one potato flower and sprinkles it onto another variety’s flower, then waits to see the resulting hybrid. Working alongside his older brother, Elmer, who helps tend the potatoes, he crossbreeds the potatoes with the highest pigmentation. So far, he’s created 70 pigmented hybrids.

Bravo looks down at the row of rubies, indigos, and even charcoal potatoes. With each new generation, the subsequent potato’s hue becomes more intense.

“Estas papas son especiales,” he declares passionately before delving into their unique benefits. The purple variety has high antioxidant properties, and the red is loaded with vitamin E and vitamin C.

Today he sells his potatoes to numerous hotels and restaurants, including to Chef Virgilio Martinez, the man behind Peru’s most regaled restaurant, Central. Bravo admits with a nervous chuckle that he did not know Martinez’s stature in Peru’s culinary world until he read an article that pegged him as the best chef in the world.

Bravo grew up running through his family’s fields, surrounded by snow-capped mountains.

Bravo grew up running through his family’s fields, surrounded by snow-capped mountains.

Upon learning that, Bravo was determined to share his potatoes with Martinez. After almost half a year of reaching out with tales of artisanal potatoes never seen before, Martinez answered back.

“Bravo’s tubers have special value for us, not just because of their quality, but because of the entire process,” says Martinez. “It is not something usually seen. His tubers have a 10-year history of transformation, whose purpose is to guarantee a better product.”

The Lima-based eatery, as well as an affiliated research center helmed by Martinez and his wife, Chef Pia León, are devoted to the culinary exploration of Peru’s biodiversity. Bravo’s potatoes fit right in and now feature prominently.

With each pigmentation comes a unique flavor profile as well. The hybrids with yellow pigment are very flavorful, slightly sweet, and versatile. Purple varieties are quite creamy and have an earthy, nutty flavor to them, whereas red varieties tend to be sweeter. Each lend themselves to varying preparations.

“Some are great to fry, while others boil well,” Bravo explains. “The exciting thing for the chef is to play around with the varieties [in] different dishes.” Using Bravo’s potatoes to make causa, for example, turns the layered mashed potatoes (accompanied by chicken or seafood salad) into a visual masterpiece of purples and reds.

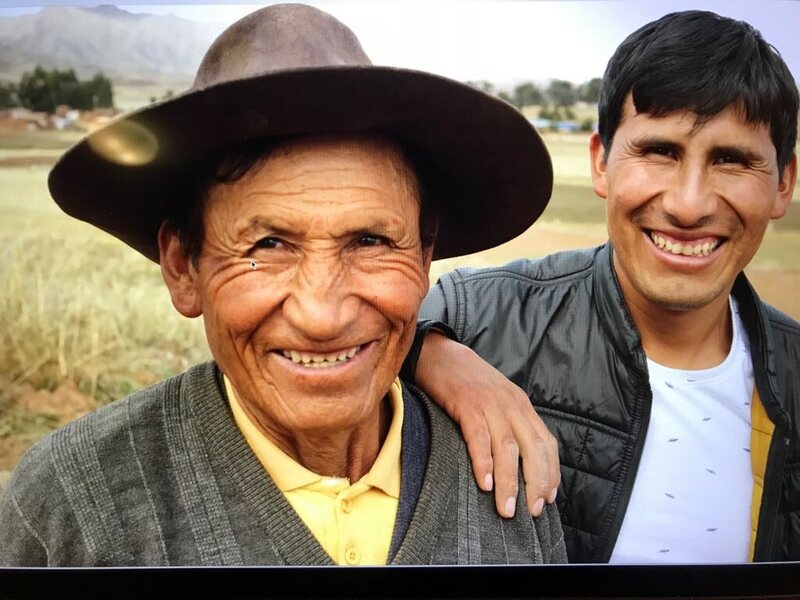

Father and son on the family farm.

Father and son on the family farm.

But Bravo has more than potatoes to offer. His boyish face makes his inquisitive nature infectious as he describes projects that include similar transformations of mashuas and ocas, as well as a wine made by fermenting these two tubers. While others coined the term vino de oca, or oca wine, he calls it Miskioca (miski means sweet in the Quechuan language). Bravo is the sole inventor of the beverage, whose flavor quickly attracted Martinez’s interest, and varies by the tuber. An almost-black variety yields a darker wine, while lighter tubers produce crisp, floral flavors similar to rosé.

In 2018, this, and his innovative potato work, garnered Bravo Summum’s prestigious “Producer of the Year” award, Peru’s Oscars of the culinary world.

“No me lo esperaba,” he says in an inaudible whisper, before repeating again that he didn’t expect it at all. Bravo doesn’t enjoy the spotlight. He’s much more comfortable on his family farm, surrounded by his tubers, working his magic one by one.

“In reality, I want to change the system,” he says. “The whole world thinks potatoes are just to fill up the belly. That’s a lie!”